'Hygiene theater' is the Covid-era security theater

Thank you for subscribing to the free edition of the twice-weekly Parallax View newsletter. All issues are free through March 22. After that, you’ll receive one issue per week. If you’d like to support our independent journalism on the intersection of health care and cybersecurity with a paid subscription, you can do so here. If you'd like a subscription option not available, please email me: seth@the-parallax.com.

Taking off your shoes before boarding an airplane, one of the hallmarks of post-9/11 security theater, is a lot closer to disinfecting your groceries to avoid Covid-19 than you might think. The excess of pandemic precautions that do not protect people from the lethal respiratory virus has created a world of “hygiene theater.”

At the heart of security theater, a term coined by Bruce Schneier in 2003, are ever-increasing, ostensible safety measures that do not make travelers safer from hijackings or other forms of violence on airplanes. Similarly, taking off your shoes indoors (to prevent tracking in the virus), disinfecting groceries, leaving packages outdoors for three days before opening them, or using painter’s tape to divide shared counter space were understandable precautions people were taking early in the pandemic, when the science behind how Covid-19 spreads was unclear.

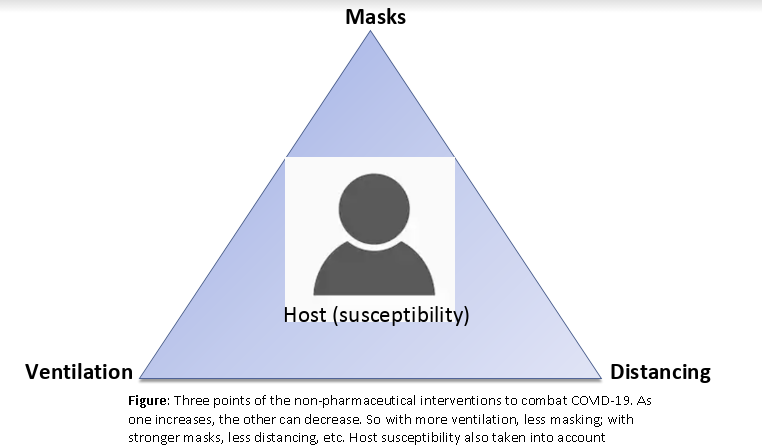

More than a year into the pandemic, we know that these chores do nothing to reduce the risk of infection while making it more psychologically burdensome to follow science-backed guidelines: Regularly wash your hands with soap or use hand sanitizer. Prioritize outdoors interactions with those outside your household over indoors interactions. Meet with small, consistent groups, when meeting in person is deemed important (in elementary schools, for example). Maintain a 6-foot minimum physical distance with people outside your household, to the extent possible. And when necessary to be in close proximity with people outside your household (in a grocery store, for example), cover your nose and mouth with a face mask.

"We should never underplay people’s anxiety, but hygiene theater makes people more anxious." —Dr. Monica Gandhi, associate chief of HIV, Infectious Diseases, and Global Medicine division, UCSF

If you’re jogging on a trail alone, with nobody in sight, wearing a mask isn’t going to protect you or anyone else from Covid-19 infection. (Putting one on if you encounter and strike up a conversation with a neighbor, however, might.) Likewise, if you are traveling in a manner in which, by all accounts (mode of transportation, companions, destination, accommodations, activities, protection measures), your exposure risk is lower than staying in your neighborhood, you are not putting yourself or anyone at greater risk of exposure upon your return.

My wife and I took a honeymoon road trip on my motorcycle up the California coast, to rural areas with lower infection and hospitalization rates than San Francisco, in October. We removed our helmets and put on masks when going inside gas station convenience stores, and kept to a strict regimen of eating in our rental accommodations (intentionally chosen to have separate entrances and HVAC systems) or at restaurants serving outdoors. We made sure to have our masks up before the server reached our table.

A health ordinance broadly restricting travel outside your area—or requiring a “quarantine” restricting in-person interactions upon returning—that doesn’t include exceptions for this type of personal travel not only doesn’t make sense but might actually increase infection risks.

“Non-pharmaceutical interventions are hard for us to do culturally, but this isn’t the same as when we didn’t have enough knowledge about the disease,” says infectious-disease expert Dr. Monica Gandhi, a professor of medicine and the associate chief of the HIV, Infectious Diseases, and Global Medicine division at the University of California, San Francisco. If families are taking science-backed “recommended precautions” when traveling, she says, and their schools likewise are following CDC guidelines for in-person education, “a 10-day quarantine after children return home is not helpful nor appropriate for a city to mandate."

By not providing nuanced, tailored recommendations in this pandemic, she adds, “fundamentally, we run the risk of skepticism and loss of public trust.”

It is so difficult to get infected with Covid-19 from surfaces that if 100 contagious people infected with Covid-19 sneezed on an apple, and then you took a bite from it, you might get infected. (Also: gross!) But you’re more likely to wind up with any number of other non-respiratory diseases before you pick up the novel coronavirus from that apple, Dr. Gandhi says.

“People who engage in surface cleaning now are doing it out of anxiety. We should never underplay people’s anxiety, but hygiene theater makes people more anxious,” she says. Instead, given that we know more about Covid-19 now than when the pandemic was starting, medical professionals, public-health officials, and politicians should focus on improving their messaging—especially as vaccination programs struggle to meet the demand for vaccinations, and how to stay safe when populations are unevenly vaccinated.

"Campaigns encouraging men to wear condoms 100 percent of the time were a total flop, and wearing an N95 mask outside at all times reminds me of that." —Maria Ekstrand, professor of medicine, Prevention Science Division, UCSF School of Medicine

Similar to threats on the Internet, the psychology of considering your “personal threat model”— a term cybersecurity experts use to describe who might be attempting to attack your phone, computers, and networks—plays an important role here as well. Age, health, pre-existing medical conditions, and concerns should factor into what kind of behaviors we engage in.

Certainly, an air-gapped computer is harder but not impossible to access remotely than one connected directly to the Internet. It also won’t be able to easily access the information, communication, and commercial services that drive today’s world. Likewise, while some people who are more susceptible to Covid-19 will benefit from adopting more stringent personal-health protections, expecting most people to adopt the infection prevention equivalent of an air-gapped computer will only decrease their participation in effective Covid-19 prevention techniques (and normal societal functions), according to Maria Ekstrand, a professor of medicine in the Prevention Science Division at the UCSF School of Medicine who has been involved in fighting the HIV epidemic since the 1980s.

Ekstrand warns that messaging and public policy intended to scare people into adhering to precautions “doesn’t work in the long run.”

“Campaigns encouraging men to wear condoms 100 percent of the time were a total flop, and wearing an N95 mask outside at all times reminds me of that,” she says, referring to a new mandate in Germany. “Any good marketing person could tell you that you need to meet people where they’re at. Meet their needs while staying as safe as possible, with honest and evidence-based guidance.”

"I don’t think there’s any evidence supporting an outdoor mask mandate." —Dr. Stefan Baral, associate professor of epidemiology, Johns Hopkins School of Public Health

But for some, adhering to the basics is a near-impossible burden, even if they want to follow them, says Dr. Stefan Baral, a Toronto-based physician and an associate professor of epidemiology at the Johns Hopkins School of Public Health.

“It is natural to want to see action in the context of something bad happening,” he says. For Covid-19 prevention, that has meant temporarily closing down schools, restaurants, places of work, places of worship, public transportation, sporting events, and nearly all in-person social interaction while reconfiguring spaces, schedules, and procedures to mitigate virus transmissions. How the virus spreads is not random, nor is it a mystery, Dr. Baral adds.

“I don’t think there’s any evidence supporting an outdoor mask mandate. There’s no significant benefit to wearing masks outdoors, as compared to addressing the significant occupational and housing problems,” says Dr. Baral, who garnered attention in 2020 for noting that closing playgrounds to children was an ineffective tactic to slow the spread of the virus, as well as harmful to children who benefit from outside playtime. Studies of who was infected and dying from Covid-19 in March and April of last year showed that in the United States, Black and Latinx minorities were disproportionately affected because they didn’t have the economic freedom to work from home.

Dr. Baral, part of a team of three physicians that has managed multiple Covid-19 outbreaks in the Toronto homeless community, blames socioeconomic disparity for the ongoing spread of the virus. While the outbreaks from March to May of 2020 could be traced to unhoused people being shuttled between medical clinics and emergency rooms to the shelters, the ones he’s seen this winter come from temporary shelter employees brought on to help manage the city’s hotels-for-homeless Covid-19 management program who lack employment protections giving them the right to stay home, with pay, when they begin to experience Covid-19 symptoms.

“I provide care within shelter settings, and what we’re not doing—what we need to do—are very specific levels of intervention. Paid leave is fundamental,” he says. “Every one of the outbreaks I’ve managed—12 so far—starts by somebody on the margins who has no choice but to go to work.”

Baral, Ekstrand, and Gandhi say that to stay out of trouble with local authorities, people should comply with public-health ordinances that may be overly broad while advocating for sensible updates, as Californians did to get public playgrounds reopened in December. However, they also argue that local, regional, and state public-health officials should be working more within the communities they serve to tailor and update messaging, techniques, and policies regarding Covid-19 to new data-based guidance about the disease. Ekstrand said very few Covid-19 public-health task forces involve behavioral scientists.

The task forces, she says, need to “keep their messaging simple, and take a harm reduction approach.”

For Dr. Baral, a big part of that requires local communities, as well as federal governments, to address racial and economic disparities driving people to go out to work and interact with others when they might be sick, and the structural racism preventing them from receiving timely, adequate health care to treat the virus, if they are sick, Dr. Baral says.

“In the U.S., it’s particularly bad because you have not much of a public-health response, combined with not much of a social-welfare system,” he says. “I can’t think of another time in history where you could buy yourself out of an epidemic.”

A Tweet to live by:

Your threat model is not my threat model, hospital edition pic.twitter.com/YHvZGCkWcs

— Nik (@hvcco) February 23, 2021

What do you know that I don't?

Got a tip? Know somebody who does? You can reach me via email, Twitter DM, or Signal secure text: 415-730-3194.

Thank you for subscribing to the free edition of The Parallax View! Learn more about our paid subscription options here.